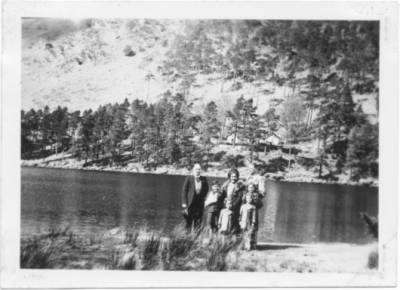

Kathy, Phil and me — Wicklow 1939

Dad was a great shopper!

One day he was down by the quayside when

a herring boat was landing its catch. It had been a good catch and,

when Dad enquired how much the fishermen would sell a dozen for, they

said.

“Ah! Sure, Sir, Just take a dozen home

with you as a present.”

Dad was overcome by their generosity, but

would not accept the fish as a gift. Instead he decided to buy a gross

of them for the princely sum of five shillings. He brought them home

and salted them and hung them up fairly tightly on four or five string

lines in front of the huge coal-fired stove in the large basement kitchen

which also served as our kitchen. There they hung for a day or so before

we began to consume them. We ate baked herrings, grilled herrings,

curried and curry-fried herrings, pickled herrings and you name it,

we had them. Annie, our maid, must have had such a job trying to keep

the smell of herrings out of the kitchen though, to be honest, I can’t

remember there being a smell of fish.

Then, on another occasion, Dad got carried

away and bought a couple of enormous baskets of oranges. We had plenty

of vitamin C, at least two oranges each, every day. The thing was that

Dad insisted on peeling them for us. He would neatly slice the peels

into segments and put them into a large earthenware jar. Every so often

he would boil the segments of peel and make things like candied orange

peel, marmalade and orange candies. The strangest thing is that I never

did get fed up with oranges and to this day I like my share of orange

vitamin C.

*****

Annie, our maid, was a lovely young lady

with a slim figure, a pretty face and beautiful auburn hair. Both of

my sisters, Kathy and Phil, had auburn hair too, and the three of them

could have passed for sisters quite easily. On one occasion just before

Christmas 1939, Annie took us three elder children to Dublin, by train,

for the day. We started our homeward journey after dark, and I can

remember so well being amazed by the street and shop lights. This was

the first European city I had seen at night and the hustle and bustle

astounded me.

In India, there was plenty of activity throughout

the day, but even when we had the opportunity of seeing the towns at

night, there were never rows of street-lamps like there were in Dublin.

In India there were kerosene oil lamps, hurricane lamps and the occasional

“Petromax” lamp, and they were usually very scattered and

mostly at eye-level or on the ground ; but in Dublin they were up in

the air AND so bright and electric. It was wondrous to see.

I must tell you, though, that in the house

in Wicklow there was no electricity and all the lighting was by gas.

I was fascinated by the woven net mantles and decided one day to examine

them closer. When nobody was about, I took a stick and again while

nobody was looking, poked at the mantle in the hall outside the kitchen.

It disintegrated into a million little pieces of ash. I was afraid

that I was in for another rollocking, for surely it was obvious that

I had broken the mantle. But I stayed quiet and waited for some reaction.

A few minutes later Annie came in to light the lamp with a taper, hardly

noticed what had happened, and calmly fitted a new mantle.

*****

Visiting Cleary’s, the big department

store in Dublin, was another huge eye-opening adventure with its escalators,

the first I had ever seen or been on and, to my eyes, the largest store

I had ever been in. I was dumbfounded at the merchandise and the different

departments. There was such a lot of Christmas bunting and so many

Christmas presents to be seen. I thought I could easily spend the rest

of my life there and not see everything, and yet, when I next visited

Dublin in the 1960s I realised that the store was a relatively modest-sized

establishment.

Annie used to go to dancing lessons once

a week and she persuaded Dad and Mum that Kathy and Phil should learn

to do some Irish dancing too. Hence it was that the three of them went

off each week to learn to do the Irish Reel. Then they would come home

and practice their steps and demonstrate to the rest of the family how

they were getting on. “Haon, do, three, caher, cuig, shay, shacht,

a Haon, do, three, caher, cuig, shay, shacht,”, they would chant

and skip about in the living room which was immediately below the Dowlings’

living room.

On more than one occasion this would set

Peggy off. The foot thumping would start and then the piano would come

in for another bashing while she sang. I used to be in “stitches”,

but Mum and Dad kept suitably straight faces and instead, nodded approvingly

at their daughters’ newly found interest and competence.

Then Mum and Dad would coax Annie into doing

a couple of other dances. She was very shy of them, but she was a great

dancer and finally, as red as a beetroot, she would step into the middle

of the floor and dance. The one thing I could never understand why

she always kept her arms down by her side. I thought it was in case

her skirts flew up and she was afraid that we might see her knickers.

To tell you the truth, I sometimes thought that she might not even be

wearing any knickers!

I think the girls, Kathy and

Phil, can still do the Irish Reel but they reliably assure me that they

DO wear knickers.

A family outing — Glendalough, 1939

Powerscourt 1939

The days in Ireland flew by. There seemed

to be so much to do. We visited Glendalough, and Dad managed to get

his arms around the famous St Kevin’ Cross to make a wish. Then

there was the Vale of Avoca and lots of Sunday walks along the Strand

and on to the cliffs and through the gorse bushes and south for a couple

of miles. Mary, at two years of age, you will remember that she was

born while we were in Mhow, India, in 1936, could do the walk with ease.

We went to see Powerscourt and I marvelled at the size of the place

and the neatness of the vast acreage of its grounds. I learned how

to make pork sausages at Seamus Dunne’s house in the bathroom,

and took the minced meat from the bath-tub and forced it through a piece

of piping until it came out the other end and filled the sausage skins.

Then we would go and deliver them to outlying houses by van.

On Saturdays, I was often with Terence Magee

when he received his weekly pocket money of six-pence and we would go

straight around to the shop owned by “Garka” Phillips to buy

half a pound of ‘broken biscuits’ for a penny. While Garka

was serving Terence, I would look longingly at the sweets and chocolates

displayed on the counter and was often tempted to “snitch”

one, but discretion was the name of the game and I was too scared to

attempt the robbery. In our family we kids didn’t get any pocket

money at all, but I knew I could always eat some of Terry’s broken

biscuits, anyway.

*****

One day, Dad and I had made our way to the

quayside because we had been invited to go out on the lifeboat for a

practice run with the crew. On the way there Dad had stopped at the

greengrocer’s and bought me an apple.

“Eat this, son”, he had said,

“It’ll give you something to throw-up instead of the soles

of your boots.”

I was indignant ; what was he talking about?

Me? Throw up the soles of my boots? I’m the expert sailor. Didn’t

I get over sea-sickness on the “California?”. But once the

lifeboat took off and started to pitch and roll about in the sea, I

was as sick as could be. Even Dad looked a bit green, but he managed

to keep his “heaving” under control, which made me even sicker,

especially when he recounted the day’s story to the family with

such an air of superiority.

But the girls, and especially Mum, were

not amused and were really kind and solicitous for my well being. Damn

the bloody life-boat, I thought ; if the ship sinks on the way back

to India I’ll just go down with it and its captain — those

were glory days and glory stories — and refuse to ride in a life-boat

again… Unless, of course, I could see a deserted, tropical island

nearby with coconut palms and a raft, and… “Swiss Family Robinson”

with their tree house came to mind and I imagined I might, after all,

take the risk in those circumstance.

Soon it was time to pack up and leave Wicklow

and head for England and Sheerness where Dad was born. Actually, he

was born in Bluetown in 1903, but Sheerness was the main town on the

Isle of Sheppy and we always referred to Dad’s birthplace as “Sheerness”.

Saying “goodbye”

at Wicklow station — 1939

We left from Dublin at the beginning of

June 1939 and arrived in Sheppey a couple of days later. We disembarked

the train at Sheerness East railway station, a tiny station which was

no more than a “halt” but it was very convenient because it

was situated right at the end of the Minster Broadway along which Grand-dad,

Grand-ma and Uncle Arthur and later, his kids, plus my aunt, Kit, lived

in a house called “Kinsale”.

Uncle Arthur, my Dad’s younger brother,

worked in the Sheerness Royal Naval Dockyard which was easily, at that

time, the largest employer on the island. He was injured in an accident

some years previously, lost an eye and now wore a glass-eye. With the

compensation he received, he bought the house and the whole family had

moved into it with him.

“Kinsale” The Broadway,

Minster — 1939

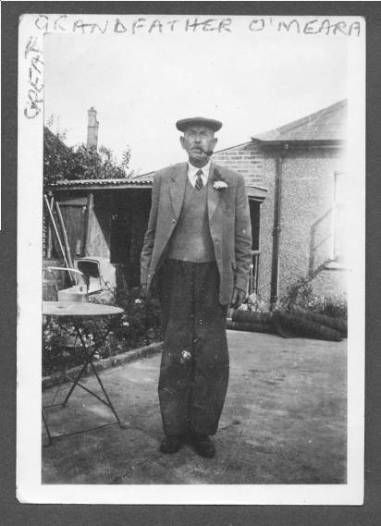

Grandpa, Dad’s father, in the

backyard of “Kinsale” — 1939

Grand-dad looked after the garden and grew

most of the vegetables which were needed by the family. Grand-ma did

the house-work and Millie, Arthur’s wife, had a job somewhere or

the other locally. Auntie Kit had a job too and was “courting

heavily”, as they used to say in those days. Her chap was named

“Ernie” Cumberland and he too worked in the dockyard. He

lived in Hope Street, Sheerness, which was a couple of miles from Minster,

but I think the bus fare was only a penny and so he was regularly up

to the house to visit Kit.

Anyway, within a couple of weeks, Ernie

and Kit were married and the reception was held at the Minster Working

Men’s Club where our family had a photograph taken with Dad proudly

standing in his army uniform. It was a very good photograph but my

stocking was crumpled at the ankle and I got one hell of a rocket from

Dad “for being untidy”.

Kit moved out of “Kinsale” and

moved in with Ernie and his mother, Mrs Cumberland, a widow. She was

a lovely, kind old “Granny”-type of lady who had a mass of

silver hair tied in a bun on the back of her head, a round scrubbed

and chubby look on her face and a permanent smile about her lips. At

lunch time, when we were attending the island’s Catholic Infants’

school for, rest assured, Dad had lost no time getting us installed

there, we kids would go around to her house and eat our lunch-time sandwiches.

The house was only fifty or so yards from the school. Ernie used to

come home for his lunch too. He would roll up his sleeves and scrub

his hands, get washed in the sink in the kitchen and then sit down to

eat whatever his mother had prepared for him. It was usually a great

pile of boiled cabbage, several boiled potatoes and a piece of meat.

After he was done eating, he would clear

the table, take out his newspaper, “The Daily Mirror”, and

give his mother and the rest of us the news. One day though, he produced

a mouth-organ instead and began to play tunes which we all knew and

sang along to.

“Can you play a mouth-organ, Patrick?”

he asked me.

|